During my unplanned layover in Reykjavik, Iceland at Christmas time, I met Victoria, an American girl and fellow drug devotée. She invited me to spend Easter break at her apartment in Montmartre, Paris. I arranged to stay several days with her in late March before flying to Norway for a two-week ski trip.

I had two goals in Paris: buy a French dress and score some marijuana. In England we smoked hashish since it was compact and easy to smuggle. Even though hashish was much stronger than the marijuana I was used to, my daily habit backfired and I was finding it harder and harder to get high. I hoped marijuana would bring back the feeling of happiness.

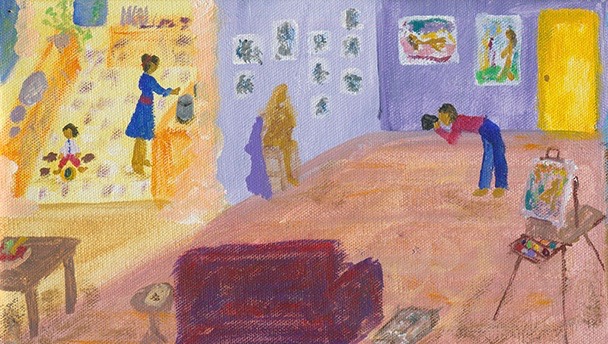

Victoria humored me and took me shopping. When I found the dress I wanted, I got confused converting dollars to pounds to francs and ended up spending all my money on the dress with nothing left for drugs. I was desperate, but Victoria had a solution: she arranged for me to pose for an artist friend of hers and be paid with marijuana. He seemed harmless, so I met him at his apartment and was relieved to see his wife in the next room preparing dinner.

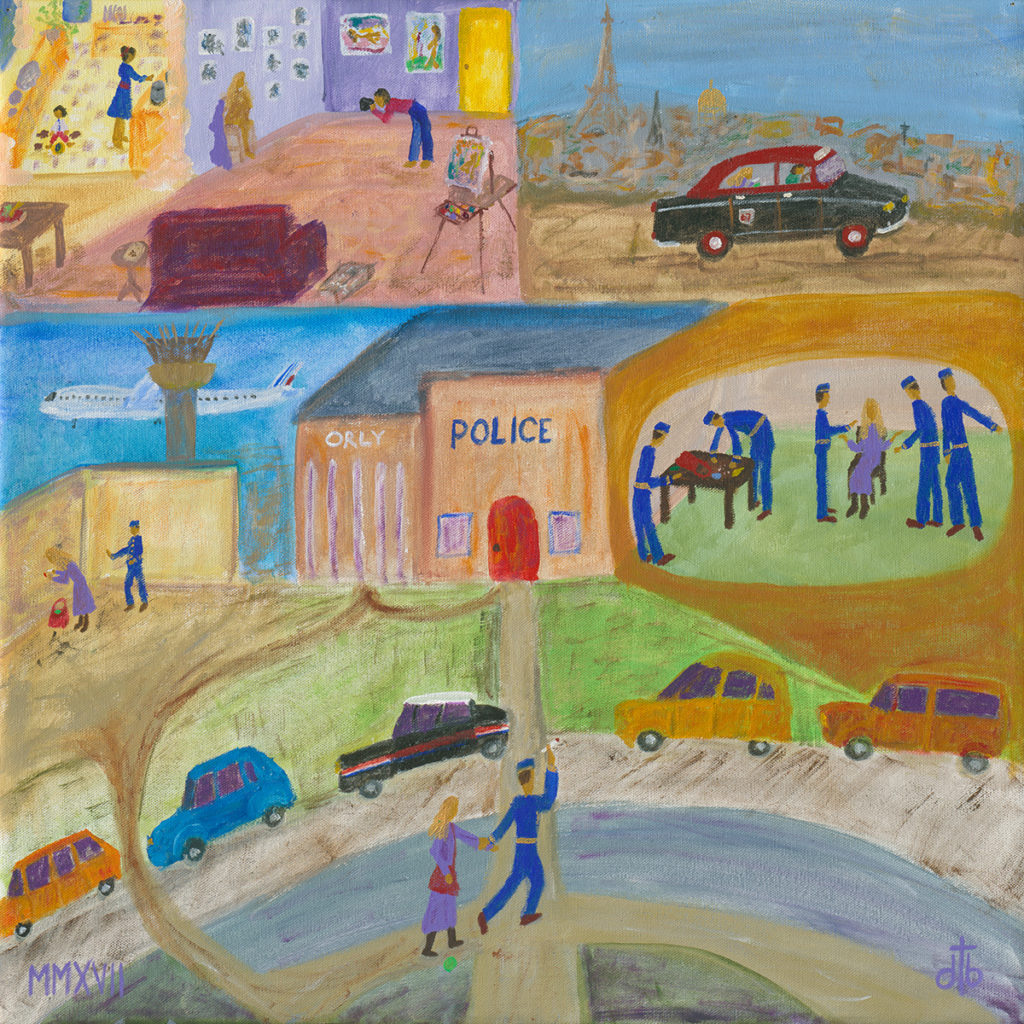

The next morning in the taxi to the airport I was eager to get high. I opened the hard candy tin where I stored the half-ounce of marijuana and rolled a joint in a yellow cigarette paper, planning to smoke it before I got on the plane. The ride was bumpy and I did a poor job rolling, so bits of leaves spilled out of the joint when I put it in my pocket.

Outside the airport I tried to find a sheltered spot to smoke, but the wind kept blowing out my match. Without warning a gendarme appeared. Immediately I dropped the joint and stepped on it. He asked what I was doing and I lied saying I was just testing my matches. I told him I needed to board my plane and started to walk away. But as I moved my foot he spotted the joint, picked it up, grabbed me by the arm with an iron grip, and demanded to see my passport. He assumed I was British but when he discovered he had caught an American, his face lit up with glee. He was so proud of his big catch that he paraded the joint above his head with one hand, his chin raised in victory, and dragged me behind him toward the airport police station.

I plunged into shock and fear. It was as if I were watching a movie of my life. Policemen were everywhere and the tin of marijuana hung like dead weight in my purse. I was in trouble. Very big trouble. Smuggling drugs across international borders meant prison.

I was led across the street and around the corner to the police station when I saw my chance. I reached into my purse with my free hand, palmed the tin, and dropped it into the gutter. The tin clanged in my ears but the hubris of my captor kept him from noticing what I had done.

The police whisked me into an examining room and made me empty my purse and pockets. My tissues, the matchbook, a Chapstick, a roll of Lifesavers were all peppered with little brown flakes. The police sent the yellow “cigarette” upstairs to their lab, then began interrogating me in French: Where was I from? Where was I going? What was I doing outside the airport? What was in the cigarette? Their questions became more specific and I was having trouble inventing lies. Although adrenaline made me remember all the French I’d learned since third grade, I claimed I didn’t understand and demanded a lawyer.

I lost all sense of time, but finally one of the gendarmes motioned for me to follow him. He led me outside the building, put me in a police car, and drove out on the tarmac to a plane—my plane. I was scared that by the time we landed in Copenhagen the French police would have received the lab results and found the tin in the gutter, and have me arrested. So I asked the stewardess for stationery and wrote a letter explaining what had happened to me. But who could I send it to? Who could I trust? Certainly not my parents. For the first time, I realized that John was my best friend.